Islands of Abandonment

The issue of vacant and abandoned buildings in the center of Athens is a complex and multi-layered phenomenon, linked to the city’s history, the legal framework of property ownership, the geographic character of urban development, and the economic and political choices of recent decades. Despite the fact that Athens faces a housing crisis and a shortage of affordable housing, it simultaneously maintains an exceptionally large stock of unused properties—a “paradox” that places it among the cities worldwide with the highest rate of empty residences.

The majority of buildings in central Athens were constructed before 1960, during a period of rapid urbanization and reconstruction. This historical legacy created a large stock of old, often listed buildings, which over the decades deteriorated due to lack of maintenance or investment. The crises of the 1980s, 2008, and 2010 accelerated the phenomenon, leading to the abandonment of businesses, the relocation of residents out of the city center, and widespread urban degradation.

At the same time, the old houses and neoclassical buildings of the city, loaded with stories and human paths, remained unused. Many of these became shelters for vulnerable people, sometimes hotspots for danger or criminality, while others simply “fell silent,” acquiring a melancholic, almost literary dimension, as documented in journalistic reporting.

One of the main obstacles to the utilization of vacant buildings is the institutional and ownership framework. Multi-ownership, inheritance complexity, the absence of strong tax incentives for renovation, and the lack of a clear legal mechanism obliging owners to use or maintain their properties contribute to the perpetuation of abandonment.

Moreover, a large percentage of properties now belong to banks, funds, or public agencies, which keep them “frozen” as investment assets. They are neither rented nor utilized, and often not even maintained. The regulatory framework does not provide sufficient tools to activate this dormant property nor impose consequences for prolonged abandonment.

Thus, the legal dimension is not merely technical; it constitutes a fundamental part of the essence of the problem.

The phenomenon is particularly pronounced in the historic center and areas that have experienced urban depopulation: Omonia, Psyrri, Metaxourgeio, Agios Pavlos, Kerameikos, and around Patission. These neighborhoods concentrate a large number of vacant buildings, many of which have significant architectural and cultural value.

Abandonment is not just an aesthetic problem; it affects the social and economic environment, creating a desolate urban landscape, limiting commercial activity, degrading public space, and reducing livability. Instead of benefiting from its historic building stock, the city lets it collapse, depriving itself of functionality and vitality.

At the heart of the problem lies a deep economic and political contradiction: in a city with rising rents and a housing crisis, thousands of properties remain empty because they are seen as “investments” rather than social goods. Housing is treated as a means for speculation rather than a necessity.

The lack of a coherent housing policy, inadequate renovation programs, absence of incentives for reoccupation, and the state’s inability to utilize the existing stock lead Athens to a global leading position in empty and abandoned buildings. Essentially, the city “bleeds” potential while possessing the building infrastructure that could economically and socially revitalize its center.

Policy proposals often include: the establishment of tax incentives for renovation, stricter regulations regarding property abandonment, social housing programs in old buildings, investments in urban regeneration, and the release of idle properties into the market.

Contemporary Ruins as a Cultural Symptom:

Athens Between Antiquity and Modernist Decay

The existence of thousands of abandoned buildings in Athens is not only an urban planning or economic phenomenon; it also has a strong cultural dimension, directly linked to the city’s identity. Athens is one of the few metropolises in the world where the ruins of antiquity coexist, almost in daily visual confrontation, with the ruins of the modern urban landscape. This coexistence creates a peculiar, almost ironic urban narrative: the ruins of the past are celebrated, while the ruins of the present are abandoned.

Many theorists of “modernist ruins” point out that abandoned 20th-century buildings function as symptoms of a culture that has lost faith in its own promise. The promises of postwar development, progress, urbanization, and the functionality of modern design gradually dissolved through economic crises, rising social inequalities, and the collapse of the idea that cities are built for the people who inhabit them.

In this context, an abandoned neoclassical building or a 1950s apartment block is not merely an “old property”; it becomes a symbol of cultural fatigue. In contrast to ancient ruins, which are interpreted as bearers of memory and continuity, modern ruins seem to represent a memory the city does not wish to acknowledge: its failure to manage its present.

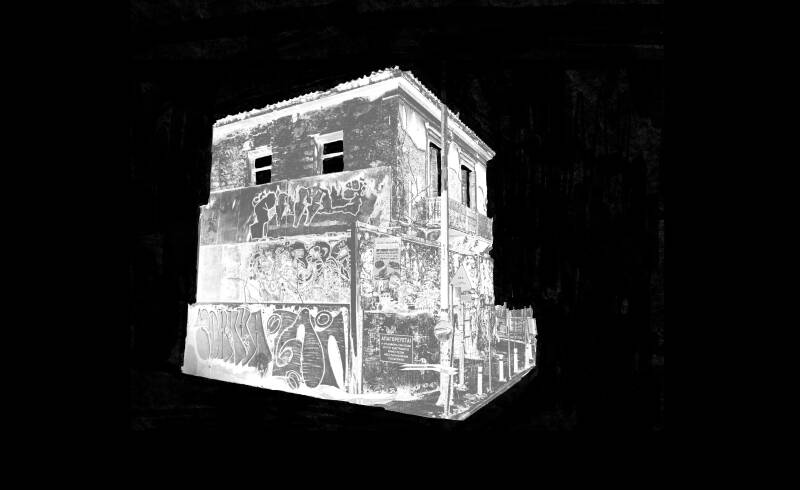

Artistic practices that isolate an abandoned building from the street view, strip it of color, and transform it into an artistic form resembling an ancient temple serve as a visual and conceptual commentary on this contradiction. They highlight the deep irony of the Athenian experience: in a city where ancient monuments form the foundation of the official historical narrative, modern ruins remain invisible, or rather, “unseen” in everyday life.

With this gesture, the abandoned building is transformed into a monument of cultural awkwardness. The urban present masquerades as antiquity, merely to demonstrate how little contemporary culture trusts its own values. The result does not merely present a remnant of another era; it presents an “archaeology of now,” evidence of collective inertia, of a culture that produces ruins without producing corresponding grandeur.

The aesthetic contrast of modern ruins with ancient ones is not nostalgia; it is critique. It indicates that the world that has collapsed is not as distant as it seems. And that, unlike antiquity, today’s ruins are not bearers of memory but witnesses to abandonment—monuments of a culture unable not to build, but to preserve.

Create Your Own Website With Webador